Pastor Keke: How one Haitian American harnessed ambition and faith to support migrants

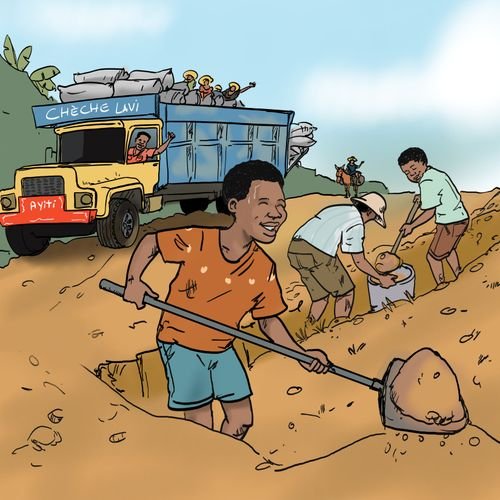

Pastor Keke, as a teen in Haiti, recruited other teens to dig long drainage canals that improved a deteriorating road to his village. These efforts were appreciated by many including women on their way to market for whom the road was so difficult to pass even their donkeys were challenged. This experience helped shape Pastor Keke’s ambitious character and a lifetime of community-oriented service.

Critical to the arrival experience and eventual integration of new Haitian immigrants is support from those who preceded them. In this section we feature interviews with accomplished Haitian Americans who, once settled, have dedicated themselves to their fellow migrants. This interview with Dieufort Fleurissaint ‘Pastor Keke’ of the True Alliance Center, reveals how faith and imagination can combine with social action and gritty self-determination to bring about positive change. Among his abilities is shifting mindsets and institutional policies to become beneficial not only for Haitians but other immigrant communities as well.

Pastor Keke, if you would please tell me about your experience growing up in Haiti and what prompted you to leave your home country for the US

As a teen in Haiti I always had great expectations for myself. I was inspired by seeing my parents who worked in agriculture - dad as a farm worker and my mother, Madam Sara they called her, purchasing crops from farmers and reselling them in the marketplace for a profit. I was the only child and she told me. ‘You are a miracle child’. Before becoming pregnant with me she went to many prayers fervently wishing for that to happen. Previously she had a daughter who died shortly after birth.

It was later as a teen at age 17 that I got involved in a church choir. Meanwhile my mom brought crops to the market with a donkey drawn cart. Since roads were always washed out we would walk behind to help those donkeys with their heavy loads. As teenagers a group of us decided we must do something so we formed a technical committee to help the town. We got some equipment, gravel and sand to dig drainage ditches alongside the roads. Every Saturday we gathered along with some adults to dig ditches on both sides so the roads would remain free of water. We also engaged the chief of police who back then lived in our community. We told him we are young people concerned about the roads and that our families use donkeys, not cars, to get to work. Though guys like the police chief had big SUV’s so had no problem with rough roads, we asked for help and he gave it. ‘Coumbit’ was a word we used meaning ‘young and old coming together’. We worked all day along with some mothers who cooked us food. We finished 5 kilometers of road in that time.

I was eager to become somebody - that was my dream - and to go from high school to college. But with economic and political trends as they were in Haiti, many of us looked to the US. As this was 1980-81 those who could travel to the US traveled there while others went to Martinique. Sadly we realized there was no future in Haiti, so at age 21 in 1981 I immigrated without documents and without parents to New York City. Back then you didn’t really need a social security number to get employed so I worked overnight at the Staten Island ferry. I was young and energetic. My job was making sure everything was ready for the morning rush. I was the baker, the maintenance guy, the cashier and in that way I was able to make a living.

While my mom had just one child, my dad had many so I had to send remittances back home - back to my mom and to other family members and friends. But after 3 years in July 1983 ICE received a tip to visit the ferry where I was working. It was only me who they caught without papers though there were also others without papers from Jamaica and from Chili. Our boss was from Argentina and hired people from other countries. They started to ask me questions - and I started to engage them in fluent English as I had studied the language from childhood as a means to realize my dream. They gave me a summons to immigration court and luckily I was not arrested. It might have had to do with my language skills. Back then they did not do expedited expulsions.

Please tell me more about your experience with work in the US and your pathway to feeling more integrated here in the US

While I was able to stay, in time it became unbearable in New York so by 1985 I looked for work in New Jersey and Pennsylvania but could not find anything. But then I did in Boston where legal status at this time was not needed. I had two cousins working at a factory in Brighton - at Cooper Industries making brakes for cars. So I landed that job while I was still young and very energetic. With overtime I made $300-400/week which to me was tons of money. In time I understood I needed to further my education so in 1987 I went to Bunker Hill Community College studying accounting at night.

Around this time I got married and changed jobs to work at Au Bon Pain. Starting as baker and cashier I then moved up to supervisor and then to managing many stores in the Boston area. This was all while still taking 2 classes at night for a double major in business administration. Working, studying and starting a family was a lot but I was determined and also lucky. The administration of President Raegan offered an amnesty under which I became a lawful permanent resident and 5 years later a naturalized US citizen.

Why and how did you transition to a career involving support to other Haitian immigrants?

When I left Au Bon Pain in 1993 I wanted to be an entrepreneur so after passing an exam I became a cab driver. I didn't have to work for anyone else! In that job I was approached by someone who told me about selling life insurance for Primerica, a company based in Duluth, Georgia with Boston offices. This included providing financial literacy classes and Haitian Radio programming. So I got licensed and with them provided my congregation with classes on financial planning, making retirement plans, handling investments, preparing taxes, etc. This later became ‘KeKe Financial Services’.

In 2000 I was ready for a new path. I started to attend seminary school and my church started to call me ‘Pastor Keke’ as I was not only teaching financial planning but freedom. I became known and the Greater Boston Interfaith Organization (GBIO) approached me to join their board as they helped immigrants back then with affordable housing, good jobs etc. What we did and still do is recruit churches not businesses. I became head of youth ministries and also helped with translation. But at the time my church, the New Pentcolstal Church of God, felt they could not combine the spiritual with social action. This was common among Christian denominations back then. I tried to convince them to change saying, ‘We need to help our people! It is too hard to have a home, job, etc.’, but my pastor said no.

Then Harry Lipman with GBIO visited my business to work with me, teach me about organizing and tell me about things I could do for our community. He came four times. ‘Since your church won't join’, he said, ‘We will partner with you/your business’. I became the only business member of the GBIO and was responsible for recruiting Haitian churches. In fact 5-6 churches joined all agreeing to social action. Our first campaign was for housing. GBIO got funding through the state to set aside units for minority families in Mattapan - and then we moved on to a remittances project helping get a better rate. At the time we were paying 10% of the total when sending money home, so I worked with Citizens Bank which agreed to cut the rate down to 2% so just $10 dollars on $500. This helped convince more Haitian churches to join. Then, because of this remittances project the rates for those from other Caribbean and Central American countries also dropped.

Keke convinces Citizens Bank officers to lower their remittance fees. They agreed and rates went from 10% to 2%. As a result families back in Haiti were better able to purchase food and other essentials in the market. To this day remittance money sent from Haitians living in the US represents a critical part of their home country economy.

We went on to other campaigns. At nursing homes 70% of CNA’s (certified nursing assistants) were immigrants, yet working conditions were not good. For instance policies included their not being allowed to speak their own language even during breaks. I got together with churches and CNA’s. We brought a complaint against nursing homes to the Attorney General of Massachusetts who then brought together the heads of nursing homes. Many of those nursing home residents with support of their children complained that they were not being served well enough because the CNA’s had too many patients. Through various meetings and actions these problems were addressed and we even got health insurance benefits by partnering with unions.

What are some major challenges you faced while attempting to integrate within the Boston/US job market? What were your priorities?

Coming here as a teenager I was grateful to have a few cousins who helped me navigate the system. Also having learned english while still young back in my country was important - I was so fortunate. For obstacles, being undocumented was a challenge but my cousins convinced my boss to hire me anyway. Color and race were also obstacles - then having no credit it was hard to find a place to rent. There was the Haitian Multi Service Center but they had very limited capacity then. So housing was also a barrier. These are all still common barriers for Haitian immigrants.

To you, what does it mean to become successfully settled and integrated?

You have to love God with all your body and to love all your neighbors as you would yourself. That is what I see in myself. In Haiti it was about helping my neighbors so when coming here I tried to do the same by helping other immigrants. I take great pleasure in helping others. This brings me full satisfaction and I can see the fruits of my efforts. That is successful integration.

How did you first meet Dr. Gabeau?

I was hosting a program on Haitian radio about finance and had heard of Dr. Gabeau, but we finally met as one day she came on my show telling listeners about her former organization, Votes for 2013. I started collaborating with Dr. Gabeau and even got children from her programs to participate live on my TV show. Then I joined as a board member of Votes 2013 and started recruiting more members.

In 2013 I stepped back from her board to focus more on programming and help around the Earthquake. We focused on the integration of Haitians. I was a liaison officer working with immigration officers bringing refugees to cities like Boston, Lawrence and Brocton which was all authorized under TPS.

Can you describe other important lessons learned through your experiences? What are your hopes and dreams?

You can’t get anything done without partnering - I didn’t believe in the old Haitian ideology about churches not engaging with social services. Another is about integration which is extremely important. Many professionals who had good jobs in Haiti could not make a successful path here. They often did not understand the system and believed myths like people telling them not to register for TPS fearing that the government would send them back. This was not true. We were getting them out of the shadows - helping them to develop professional skills and to get better jobs.

Currently I am with the Gordon Center for Urban Ministerial Education where I earned a Master of Divinity, Master in Practical Theology and I am now a candidate for Doctoral ministry (DMIN.) I have been exploring questions like how do you provide resources to immigrants? Does your church connect? Thank God for IFSI because I’ve connected with IFSI from day 1 working closely on all areas from legal and housing assistance to advocacy.

Do you and your organization have other social action commitments?

I chair the Haitian Americans United (HAU) celebrating Haitian identity and the True Alliances Center (TAC) which is becoming a part of Equity Now. We started with flu shots for the African community and we bring health centers services directly to Haitian food pantries. We also were educating people about the US Census as people were afraid. We worked right alongside IFSI on these issues. Then right around the corner and covid hit.

Were there important lessons, insights or innovations that helped with your career and becoming a minister? Let's talk more about this and make a list together.

Build your own capacity. That is primary and key. I learned about this as a teen repairing roads, but it is never too late to start or resume this focus in life.

Support others. While continuing to build your own capacities comes first because you are then better able to support others, individuals and in communities.

Partnerships are everything. Too often people try to go about things on their own - individually or focused on just their organization.

Be practical. Think about how organizations can continuously improve from handling technology and, finances to personnel and cultural competencies/linguistics. They can then be more effective and able to benefit their communities.

Role of the church. The first place Haitian immigrants come is to a church and from there to multi-service organizations, ideally a ‘one-stop’ center with Haitian cultural expertise. It is important that there is a direct link between churches and these organizations.

Final advice: Behave like a ministry. I support service organizations in their quest to be practical while also spiritual. That is my ministry.

By The IFSI Immigrant Navigator Team: Dr. Mario Malivert, Makendi H. Alce, Larry Childs, Angie Gabeau, Hidalgo Delbeau, Nick Carstensen, and Giulia Campos

Illustrations: Teddy K. Mombrun

Lead journalist and interviewer for this story: Larry Childs